The Yellow Vest protests that have convulsed France for the past few weeks, leaving chic Parisian neighborhoods smoldering, are making environmentalists nervous.

The protests began in reaction to President Emmanuel Macron’s announcement that a planned increase in taxes on gasoline, part of an ongoing ambitious effort to combat global warming, would take effect in January. Though the tax was favored by Parisians, who have access to efficient public transportation, it was seen as a provocation by struggling residents of the country’s rural and suburban areas. (“The taxes are rising on everything,” a rural retiree told a reporter from this newspaper. “They put taxes on top of taxes.”) Caught off guard by the intensity and popularity of the protests, Mr. Macron backed down on the tax hike, but not before the Yellow Vest movement morphed into a leaderless, anti-establishment revolt that now threatens his government.

As with working-class support for the faltering coal industry in the United States, the question arises: Is environmentalism a boutique issue, a cause only the well-off can afford to worry about?

Some social science suggests the answer is yes. In a landmark 1995 paper, the sociologist Ronald Inglehart observed an intriguing pattern in public support for the environmental movement. According to a public opinion survey he conducted in 43 nations, the countries where large percentages of the population supported strong environmental policies shared two characteristics: They were dealing with major environmental challenges (air and water pollution and species conservation were among the top priorities at the time) and they were affluent.

Mr. Inglehart argued that citizens were apt to prioritize environmental concerns only if they were rich enough not to have to fret about more basic things like food and shelter. Environmentalism was part of a larger “postmaterialist” mind-set, focused on human self-realization and quality of life, that was naturally to be found in the world’s economically advanced societies — and especially among better-educated, wealthier citizens. Mr. Inglehart anticipated that growing prosperity, rising education levels and increasingly dire environmental circumstances would translate into the further spread of environmental consciousness in the years to come.

In some ways the situation in France fits this theory. France is wealthy and well educated. And environmentalism is big there. A 2017 study, for instance, found that 79 percent of the French population believes climate change to be a very serious problem. It is plausible to think that some of the anger the Yellow Vests are unleashing on Paris revolves around the cultural gap separating those French citizens privileged enough to be able to devote time, attention and money to matters like the environment from those not as fortunate.

Thought-provoking as Mr. Inglehart’s thesis is, however, it’s not hard to identify weaknesses. Here’s an obvious one: The United States, like France, is a prosperous country with a well-educated population. Yet according to a survey conducted this year by the Pew Research Center, only 44 percent of Americans say they care a great deal about climate change.

More recent research bolsters this skeptical view. Work by the sociologists Riley Dunlap and Richard York, based on a wider range of data, turns Mr. Inglehart’s finding on its head: They have discovered that the publics of poorer countries facing imminent resource loss from environmental destruction often hold the strongest pro-environment attitudes. For example, the island nation of Fiji — which stands to be decimated by global warming, rising sea levels and storms — ratified the Paris climate agreement on a unanimous parliamentary vote before any other nation did.

Another study, by the political scientist Matto Mildenberger and the geographer Anthony Leiserowitz, has found “no evidence” that people became less attuned to climate change when their economic prospects dwindled after the 2008 financial crisis.

Mr. Dunlap and Mr. York emphasize the contingency and variability of public support for environmental causes and practices. How much backing there will be — and in what quarters — depends on the specific environmental, economic and political conditions countries face. Environmental protection efforts can advance if the environmental movement acts strategically.

The notion that there are few hard-and-fast rules when it comes to public support for environmentalism has influenced the response of environmentalists to the Yellow Vest protests. While raising taxes to reduce fossil fuel consumption or fund green energy transitions is essential, they say, depending on how and when such policies are proposed, they may spur a backlash. So smart rollouts and messaging matter. Mr. Macron’s environmental policies, for example, were announced from on high, without meaningful input from all the communities that would be affected.

Environmentalists insist that there is no reason in principle why a more effective communications strategy could not be found to pull together urban dwellers and the rural working- and lower-middle-class in a broad environmental coalition. The fact that the French public is sympathetic to the cause of the Yellow Vests but also concerned about the climate shows that the protests were never really about the environment in the first place.

Such a perspective is comforting. But it arguably understates the magnitude of the problem the environmental movement now confronts. Yes, contrary to the theory of postmaterialism, the well-off aren’t the only ones who care about climate change and the environment. Yet in many of today’s capitalist democracies, class and status resentments, fostered by rampant inequality and whipped up by opportunistic politicians, have developed to such an extent that issues like the environment that affect everyone are increasingly seen through the lens of group conflict and partisan struggle.

Differences between urban and rural, new economy and old, college educated versus working class and cosmopolitan versus local loom larger than ever. Although the research of the sociologist Dana R. Fisher shows that in the United States, climate change activists have been working to diversify their ranks, the trust needed for truly large-scale environmental coalition building is wearing thin.

Thus a different interpretation of the Yellow Vest protest may be warranted. Without a concerted effort to address inequality — which some in the environmental movement consider someone else’s department — the bold policy changes needed to slow global warming risk never getting off the ground.

Neil Gross is a professor of sociology at Colby College.

Link

to original article.

Dallas Goldtooth, an activist with the Indigenous Environmental Network who helped stop the Keystone XL pipeline, is still advocating for sustained demonstrations and non-violent actions.

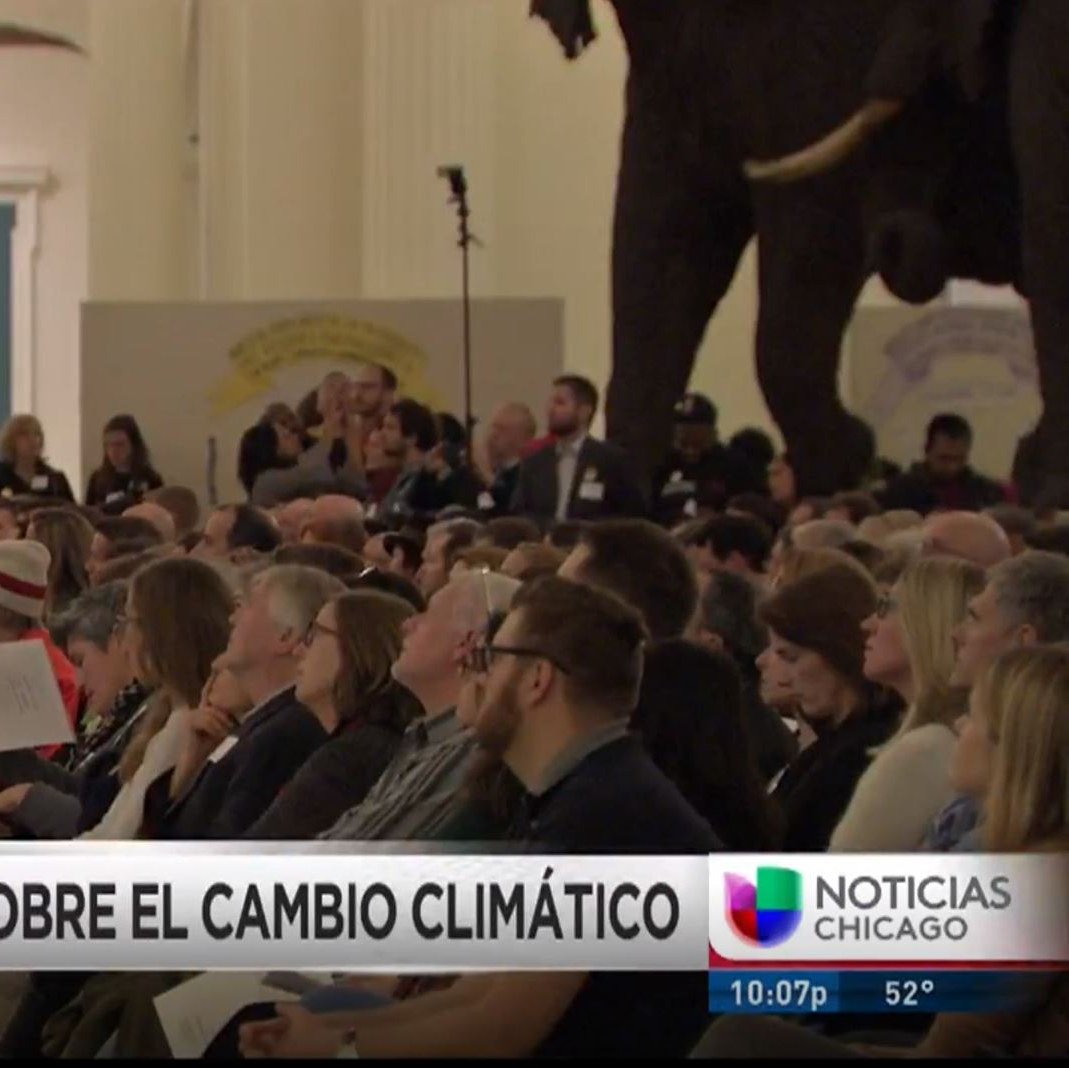

“We need a story of change…of resistance,” he told a gathering of close to 1,500 civic leaders, community members, and representatives from 70 civic and environmental organizations that attended the Chicago Community Climate Forum, held Dec. 3 at The Field Museum.

The centerpiece of the forum was the unveiling of a Chicago Agreement on Climate and Community. The agreement outlines a set of principles and commitments by the city’s neighborhoods, institutions, and organizations to curb climate change. Just as the Paris Agreement facilitates collaboration among nations of the world, the Chicago Agreement offers a way for community members and local organizations to contribute to practical climate solutions.

Members of the Green Community Connections/One Earth Film Festival leadership team helped conceive and plan the Climate Forum, which took place on the eve of the North American Climate Summit organized by the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate Change and Energy. Mayors from around the world convened in Chicago Dec. 4-5 to discuss municipal commitments to the Paris Agreement to curb climate change.

A call to action

The forum was, in part, a response by Chicago environmental advocates to plans by the U.S. to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. They decided to mobilize and convene discussions for taking local action. Planners spent about seven weeks pulling together funders, speakers and a guest list. When RSVPs surged beyond expectations, the planning team had to request a larger space within the cavernous museum.

Generous support for the forum came from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Based in Chicago, MacArthur is one of the nation's largest independent foundations. Since 2014, the foundation has made $200 million in grants to accelerate climate response and bring new voices to the fore.

In opening remarks, Julia Stasch, MacArthur president, said cities, like Chicago, are on the front lines of climate action. “Cities represent climate vulnerability, but also opportunity,” Stasch said, noting that 54 percent of the world's population lives in cities.

“There's a myth that we're safe because we live in the Midwest,” she continued. “No hurricanes, forest fires … But our economic productivity is threatened. Chicago is the 6th worst city in the U.S. for allergy impacts due to ozone.”

In his remarks, Chris Wheat, chief sustainability officer for the City of Chicago, referenced climate change’s “disproportionate impact on certain communities” and the need for intersectionality when creating policy.

Newspaper columnist, political analyst and Field Museum trustee Laura Washington was the evening’s mistress of ceremonies.

People power

Keynote speaker Mustafa Santiago Ali, a former senior adviser at the Environmental Protection Agency, who now serves with the Hip Hop Caucus, delivered part pep talk and a rallying cry, telling the crowd: "It's time to get focused to make necessary change. If we win on climate, we must also address the most vulnerable communities." Quoting his grandmother, Martin Luther King Jr. and others, Ali ended his remarks by asking audience members to hold up their hands and yell, “Power! We have power unless we give it away.”

Following Ali, who has trained more than 4,000 people across the country in environmental justice techniques, was a panel comprised of local environmental activists, including Goldtooth.

One of the panelists, Anthena Gore, a project coordinator with Elevate Energy, shared a painful and personal story centered on environmental justice issues. She recounted being diagnosed with lead poisoning when she was 2 years old and how her family dealt with the expensive hospital bills. Gore finished by asking: "Who is the two year old you are trying to reach today?"

The youth dance and spoken word ensemble Kuumba Lynx ended the program with a performance of their “Black B4 Green” production, a powerful commentary on racial and environmental injustice. The program also included a short video featuring voice from a cross-section of Chicago’s environmental activism community.

A reception featuring food and music rounded out the evening, with interactive “Co-Lab” (collaborative) spaces set up that fostered dialogue, learning and networking, along with tools and resources to help people start taking action on climate change.

In all, a festive air characterized the event, even focused as it was on the serious issue of climate change.

Laura Derks explains duties to 'Co-Lab' volunteers.

Laura Derks, a member of the Green Community Connections/One Earth Film Festival’s Core Team, had spent many hours helping plan the forum. As she surveyed the crowd of over 1,000, she reflected that the intensive work of creating such an unprecedented event was worth it.

“Helping a group of 75 volunteers staff the ‘Co-Lab’ space, where attendees could connect, discuss, and plan, during the Chicago Community Climate Forum at The Field Museum was exhilarating,” she said. “The enthusiasm of the volunteers, the energy of the attendees, and voices of the program participants filled the massive Stanley Field Hall and offered promise to future collaboration on affecting climate change at the grassroots level.” - Cassandra West

Link

to orginal article.

On the eve of a climate summit that will bring mayors from cities all over North America to Chicago, MacArthur Foundation President Julia Stasch, Field Museum President and CEO Richard Lariviere and ecologist Abigail Derby Lewis will be among a lineup of speakers Sunday at a forum on climate change.

The Chicago Community Climate Forum, which will run from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. at the Field Museum, will bring together local leaders and activists to discuss the work they are doing at the neighborhood level and ideas on how to make it a part of larger public conversation. The event is free and open to the public.

The keynote speaker will be Mustafa Santiago Ali, a former senior adviser at the Environmental Protection Agency, who now serves with the Hip Hop Caucus, a nonprofit that works to create a network of young grassroots leaders.

Other speakers include Kimberly Wasserman-Nieto, of the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, Toni Anderson of Sacred Keepers Sustainability Lab, the Rev. Booker Steven Vance of Faith in Place, Anthena Gore with Environmentalists of Color & Elevate Energy and Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network. The Kuumba Lynx performance group and the Noteworthy Jazz Ensemble are each scheduled to perform at the event.

On Monday, mayors from the U.S., Canada and Mexico will gather in downtown Chicago to discuss new programs they will implement reduce carbon emissions.

Since President Donald Trump announced plans to withdraw from the sweeping 2015 Paris Agreement last June, American mayors across the country — including Rahm Emanuel — have publicly stated a commitment to curb environmentally harmful emissions on their own. Negotiated by nearly 200 countries and championed by former President Barack Obama, the agreement commits nations to reduce greenhouse gases.